Interviews

The Resurgence of Indie Cinema. An Interview with Graham Swindoll (Kino Lorber)

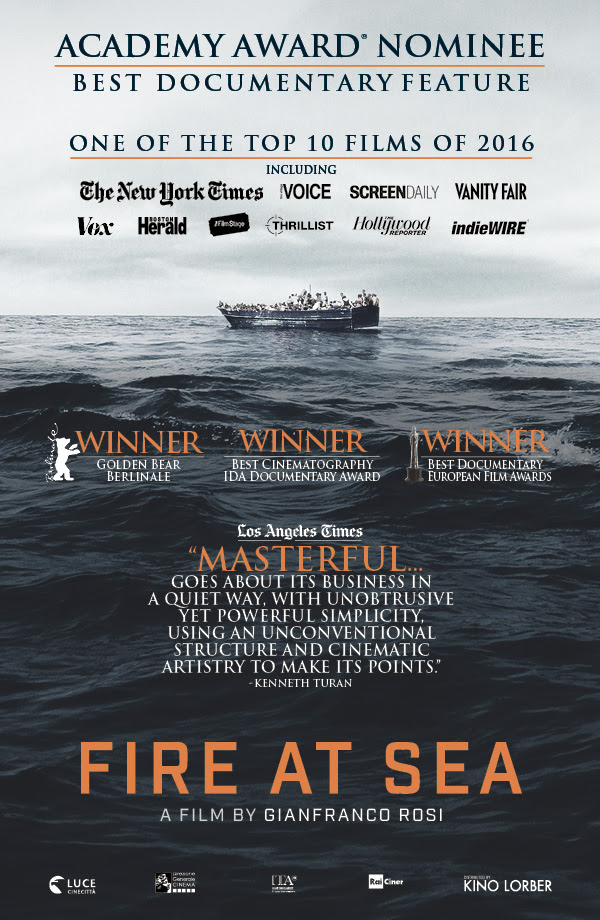

Kino International was a film and video distributor, founded by Bill Pence in 1977, and acquired by Donald Krim in the same year. In 2009, Kino International merged with Lorber HT Digital to form Kino Lorber. The company, based in New York City, specializes in arthouse films, low-budget movies, documentaries, classic films, and world cinema. In 2010 and 2016 Kino Lorber distributed in the US two Italian documentaries: The Four Times by Michelangelo Frammartino, and Fire at Sea by Gianfranco Rosi, which won the Golden Bear at the 66th Berlin International Film Festival and the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. On the afternoon of March 20, 2019, together with my colleagues Marco Cucco, Emiliano Morreale and Massimo Scaglioni, I had the opportunity to meet Graham Swindoll, Director of Theatrical Sales of Kino Lorber, at his office, on 333 West 39 Street, in New York City. We did an interview mostly focused on the case of Fire At Sea, for which he handled the theatrical and festival bookings.

In our research corpus, we have just two documentaries and you distributed both of them in the US: is this the result of a specific way of choosing types of Italian and/or European films?

Kino Lorber, in general, does different types of releases, but we do a lot of documentaries, as well as foreign language narratives and some American independent films, although that’s less frequent: even when we do American films, they are usually documentaries. I don’t know if it’s 50-50, it depends on the year, but I think, compared to a lot of US distributors that maybe don’t do any documentaries, or very few, we are more in the middle. I don’t know if that’s the reason why in this case, but we certainly do both types of films.

You used to work with some festivals, too…

Yes, a lot. To give you my exact role: I do the theatrical bookings, so booking the films in the theatres, and also festival bookings, so it’s kind of connected: they are two stages of the same release. Usually, you firstly go through festivals and then you go through theatres. The US is a physically large country, so there are many cities (even big cities) that don’t really have a theater that would play a foreign language film. Or maybe they would play it once, but not for a week. But they may have a festival that actually has a bigger audience, and would make more money than a theater would. So, festivals and theatres are kind of connected in the releases, specifically of foreign language films in the US.

Which are the most important festivals for foreign language films in the US?

The most important overall festival for sure in the US for anything is Sundance. It’s obviously not Cannes or Venice, but it’s the closest to this kind of markets. It’s very American-centric; it’s an international competition, of course, and sometimes it has really good films, but in my experience the best foreign language films are usually seen abroad, like in Cannes or Berlin or Venice or Locarno, rather than Sundance. Although, for instance, The Wound, the South African film, is really excellent and that premiered in Sundance. It’s just the festival that gets by far the more press and I think it’s the only festival that people outside of cinema are aware of, everywhere the country. So certainly, as far as, say, putting on a trailer, it’s the most useful for selling a film and for having press around the film. It’s not in the US, but the other important market is in Toronto, of course. Beyond that, it becomes a little more specific to the type of film; there is Tribeca and South by South West, again much more focused on American films than foreign films. Then there are other prestigious festivals that are not so much “première” festivals, but that nonetheless take a lot of major films and they get a lot of attention, even regionally and nationally, like New York Festival, the AFI Fest in Los Angeles, the International Film Festival in Chicago (very popular within its region, but it doesn’t go out very much). There are many middle-size festivals, but only a couple that have a national footprint.

Documentaries can have a whole other circuit, because there are many festivals that are documentary-focused or exclusively documentary festivals, some in Canada, some in the US. There is Hot Docs in Canada, a very important festival for documentaries, and Camden in Maine is another important festival – not a big one, but other programmers pay attention to it. Then there is another festival that has become very important in the last 5-6 years called True/False, in Columbia, Missouri, which is a small college town that started this documentary festival, that a lot of documentary critics and programmers go to. It can be a very useful and important festival, even though most people have never heard it. So, it depends a lot on the type of film and the type of path you’re trying to take. A film like Fire at Sea, even though it’s a documentary, it’s also the winner of the Golden Bear, a film by Gianfranco Rosi, an established, well-known, international director. Even though he previously had no very large releases in the US on the festival circuit he was very well-known, and his films were very well seen. And I think his previous films were quite well released within Europe – though I believe Fire at Sea was released much more broadly than his previous ones. I remember at one point the sales agent was counting how many countries he sold to, and it was something like 70.

Film posters on the wall of Kino’s office in NYC

Can you say something about the way in which you worked with Fire at sea? Perhaps starting with the Berlin Film Festival, and then what you did…

I can’t say anything about the acquisition, because it wasn’t me, it was my superiors, but I think we didn’t get the film at Berlinale. It was a little afterwards, because there is often this back and forth on trying to understand how it is going to work, then he won the Golden Bear and suddenly the prices went up! The film got a huge amount of attention in the US, but it’s still a film that is hard to make money with in the US. Ultimately the admissions in theatres were quite good, for a foreign language documentary, but it wasn’t millions of dollars, rather hundreds of thousands of dollars. We acquired it thinking that it was a film that had a chance to gain an Oscar nomination, because of the content, because of the quality of the film, because of the reputation and connections of the film-maker and because of the Golden Bear. It was positioned in a place we’re always looking for, not only financially important but also historically important in the conversation on cinema for a long period of time. And it’s important because we care about films and film history, but it’s also an important part of building the reputation of the company and helping us to work on other acquisitions, and our position, working on films that can be competitive in this way.

From that moment, we knew there was a real possibility with the film, so a lot of the decisions about how it was going to be positioned were made considering an awards campaign, not just a release. We were not necessarily making decisions in an absolute financial sense, but because it made sense to put the film in front of the right people, to help it move towards that nomination – which ultimately it received, and we were all happy about it. It wouldn’t have been a massively different release, but definitely the latter moments of its release would have been very different if we weren’t working in concordance with an Oscar nomination. Even the date that we opened the film in the US was partially to do with trying to open it near enough to voting (in October, because the shortlist comes out in November). If you have a huge film and a lot of resources you may push it even later than we did, but we also knew it was a foreign language film, a film that was going to need to build its reputation within the US, so we wanted to take it a little bit earlier and have time. Sometimes what you see people do is to do a main release much closer to the Oscars. So, because they think it’s going to get the nomination, they do what’s called a ‘qualifying run’ in the fall before – since you have to have a run in the year before the Oscar – so just a week in New York and a week in Los Angeles. People that do these very small releases try to make audiences not realize it was released, because they’re basically just doing it for the paperwork. It’s quite silly and we didn’t do like this. We released the film properly, all for the New York Film Festival, and there was a lot of attention put in to trying to get into the largest and most prestigious festival, both as a documentary film and as a foreign language film, because I think the film was received in both ways. More broadly as a European film, I think.

It’s interesting because it’s difficult: you can get a lot of attention from festivals and a lot of attention from press around films with this kind of subject matter, such as migration and international socio-political issues. Last year we had a documentary that was also nominated for an Oscar, also foreign language, called Fathers and Sons, that was a fantastic film but it was much more difficult than Fire at Sea. The subject matter wasn’t enough to get people to buy a ticket, so you are running up against the industry and how the exhibition works. Most people in the US don’t go to the movie theatres to watch a movie with a subject like that, perhaps they would prefer to watch it on television or via streaming, but you have to find a way to get it out of the theatres if you are going to have to take it seriously as a film. It’s kind of a strange situation.

There was a re-release of the movie after the nomination…

What happened, as I recall, was that the nomination came out in January, right at the beginning of Sundance, and then suddenly we were thinking “all right, now we’re ready to blast all the theatres” and the movie theatres were thinking “this movie seemed too difficult but now we’re interested”. So you get another 30-40 screenings, whether to make money or not (again, complex), but the film kind of came back to the spotlight.

Except for the festivals you mentioned before, would a movie with an international distribution, like Fire at sea, be released only in big cities like New York or Los Angeles?

Yes, it’s a little bit irregular, because it’s mostly in larger cities but there’s also a circuit of independently owned and operated theatres, generally called ‘arthouse theatres’ in the US. Most theatres, 95%, are commercial multiplexes owned by four or five companies. We stream sometimes with multiplexes, but it’s quite rare. In fact, there’s some major cities that don’t actually have an arthouse theatre, even with a population of several millions, and then there are some quite small towns that have a very vibrant, active, art theatre. Generally, you could say ‘yes, a film like Fire at sea is going to play in New York, Boston, Chicago, Washington DC and Los Angeles, but it will also play in smaller cities where you wouldn’t expect to get a film like this, because there’s a community that cares about it. A lot of it is guided by where the theatres are, and the programmers are that pay attention to this kind of cinema and its audience. As a distributor you can, of course, help to build an audience, but I think a lot of it comes down to finding and working with programmers who interact with local communities, because we have an office in New York and we’re trying to release this film in 50 cities and we don’t know anybody in Nashville – but the programmer in Nashville can help figure out what’s the best way to release this movie there. And whether to do a normal run, a weekend or a special screening. It’s really very dependent on the film and the place. It’s difficult because there used to be a much larger market for these films 40 years ago, but it was chipped away by the multiplexes.

Was there actually a reduction of these arthouse films?

At some point there was definite a pull back. There was a time in the ’60s and ’70s when foreign language films did get wider releases in the US, but then when multiplexes became stronger and bigger and more monopolized, things shifted away from that. Now I think there is not a renaissance, exactly, but a little resurgence of independent theatres in the US. It’s always heartening because there are new theatres that all open, like this small city, Akron in Ohio, that has a theatre that plays many interesting things, all because of one programmer in Cleveland, Ohio, which is a middle-sized city but plays every foreign language film. You could live in Cleveland and watch everything that there’s in New York. But it’s one person who does it.

Columbus, Ohio, is a very special place too: the Wexner is an important institution both because they have amazing programmers and because they have a lot of resources, thanks to the university and the donors which helped make it what it is. And there’s another institution in a place you wouldn’t necessarily expect: the Indiana University Cinematheque, in Bloomington, Indiana, which is like Columbus, a university town. They have a well-founded, well cared-for and operated cinematheque and they screen in 50mm every day, in Bloomington, Indiana. Anywhere else in Indiana you wouldn’t even see a major foreign language release. A lot of it is guided by chance, especially regionally, when there’s an institution that can take care of this and bring into audiences.

In your experience, is there anything specific about distributing Italian films, in terms of the relationship with Italian distributors, sales agents or just for the content?

We ultimately release films for larger countries, like China or South Africa, or most frequently France, because they produce the most films and there’s a certain connection in a lot of American minds between French cinema and art cinema. Everyone is different, and we always try to see if we can connect to specific audiences. Italian immigration to the United States happened so long ago that I think communities are not that connected to Italy culturally anymore. When you’re working with an art film it’s always complex – and the same is true of Italian films – trying to connect with a population that maybe wants a mainstream film. There are Italian cultural organizations that help to connect with Italian film funds for support and things like that, and certainly, a lot of support for the release of Fire at Sea came from Italian funds. But on the ground, the audience level is not that strong. And that’s true for a lot of films, not just Italian. Working on a Chinese film recently, it was interesting to try to connect with Chinese communities because the film has been released in China, people have heard of it and it’s a very big audience – that doesn’t come to see, say, French films, for instance. The Italian-American audience is very much Italian-American, rather than Italian, especially in New York, and so I’ve never really seen that same level of engagement. As far as working with foreign distributors, we usually have fairly limited interaction; sometimes, we sell them materials, we buy some posters and trailers from them. It’s almost always through the sales agents, who more often than not, regardless the nationality of the film, are French! It’s more getting the materials, some broad discussion of strategy, but usually once we’re into the release we’re operating on our own, largely.

Do you work with much Italian cinema of the past, or classical cinema?

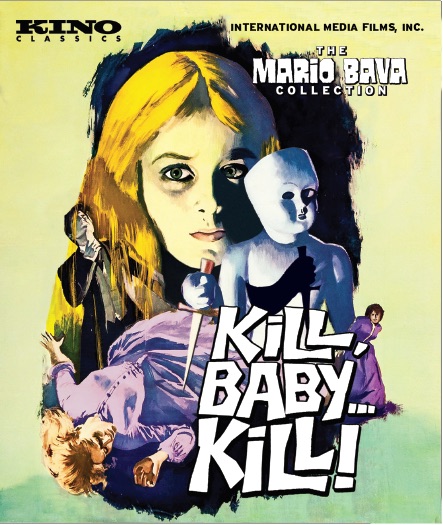

Yes, we release a lot of classic films on DVD, VOD and actually in theatres – my colleague Jonathan Hertzberg does all of our bookings for repertory films. And we do a lot of Italian cinema. In 2017 we did a re-release of seven Lina Wertmüller films, in theatres, and in late 2017 or 2018 we did a re-release of Kill Baby Kill by Mario Bava. So we are always dealing with classical cinema and, financially, the “backbone” of the company is home video sales, and we have a lot of classic films on video sales. We also do a lot of releases on DVD and Blu-Ray of Hollywood films, for different reasons. A lot of the studios have actually moved back from releasing so much on disk, which gives more access to better films that we can put onto Blu-Ray. I think there is a big overlap between audience for contemporary art foreign films and classic foreign films, they definitely have a similar audience: people who think of films as art (that is really not the norm in the United States).

Do you work with OTT providers, like Netflix or Amazon? Do you think it could be a way to reach younger audience for these films?

Yes, we work with OTT providers, but about the audience I don’t know. I hope so. It’s definitely becoming an increasing and important part of the business model to exist, because things like home video rentals used to be an important thing and now they don’t even exist, so I think Netflix and Amazon have replaced the kinds of sales you used to do with a video store. Those kinds of sales are important for any kind of release: a sale to Netflix or Hulu can give the film a kind of security. If you know you have this sale and you know you won’t lose money on the release, even if it doesn’t take off, you can position and work on the release, but you don’t expose yourself to losing everything on something. It can be a really important way of stabilizing the system, because, of course, when you’re working in film distribution most films don’t make money, it’s just the nature of the system. So, you need to find a way a balance to keep moving and unfortunately it doesn’t have very much to do with the quality of the film, in my experience.

Did you re-cut the trailer of Fire at Sea?

We designed a new poster, for sure, and I think we cut our own trailer. I don’t think it was even re-cut, but cut from the beginning. Usually, if we buy a foreign release trailer sometimes we put American, French or Italian press around, but in the case of Fire at Sea, where we were also really trying to position it for the Academy Awards and for this kind of prestigious reception, we felt it was important to do the arts and the trailer with that in mind. So, we did that stuff from the ground, although I know there was a lot of involvement from Gianfranco, so I think you will probably see some similarities regardless. He lived here for a couple of months, then he came back for a month when the nomination came, he was mostly in LA but he was back and forth. He was extremely involved in the promotion of the film and in fact we also organized a retrospective in New York at Bam Theater, with all his previous films, and created a collection in Blu-Ray of all his work (including films that have never been shown in the United States). It was a full project.